Ontario needs to ensure that its carbon pricing approach enables its cities to accelerate reduction of urban emissions sources.

Consultations regarding the Province of Ontario’s proposed climate strategy are underway, including two public meetings held at the downtown Toronto YMCA last week. If the public response at these meetings is any indication, there are a lot of different opinions on the best way to design an effective carbon pricing strategy.

Carbon Tax

Many were favouring BC’s revenue neutral carbon tax approach, also known as a carbon fee and dividend approach, where all the funds collected through the tax on gasoline, natural gas and heating fuels are returned to citizens and businesses through tax reductions and rebates.

While many British Columbians were sceptical that their carbon tax would really be revenue neutral, the resulting tax cuts have actually been larger than the tax revenue, making it slightly revenue-negative. Now a majority of British Columbians (52%) continue to support the policy, which has survived two election cycles. Starting low at $10/tonne and gradually scaling up to $30/tonne over 5 years helped reduce opposition; however, announcing a longer-term schedule of price increases (e.g. to $50/tonne by 2018) would have enhanced impact and provided businesses and consumers with longer-term certainty.

A recent report by Clean Energy Canada delves into the BC experience. It shows that, overall, the carbon tax has helped the Province to achieve its 2012 emissions target (6% below 2007 levels), both because of the price signal and the official signal it gave that carbon reduction was an important, economy-wide priority. Meanwhile, economic growth in BC has outpaced the Canadian average, demonstrating that carbon taxes are not the job killing economic disaster opponents claim.

Cap & Trade

What a carbon fee/tax does not provide is certainty about emission reductions. They way Quebec has moved ahead on carbon pricing is by adopting a cap & trade system, where the government sets maximum allowable carbon emission limits and then provides emissions allocations to specific emitters in the form of emission permits, with the total amount of permits being equal to the cap.

Emitters that produce less than their allowed emissions can sell the ‘excess’ reduction to those entities that exceed their permitted emissions, creating a carbon market. Total emissions must stay beneath the cap, which in turn is reduced gradually over time on a predictable schedule, so that emitters are motivated to continuously innovate to bring down their carbon emissions.

While most cap & trade systems only apply to major emitters, Quebec’s system expanded in 2015 to include all suppliers of gasoline, diesel and natural gas, and now covers 85% of the province’s emissions sources. This is critical to the impact of the policy because Quebec’s largest source of GHG emissions is the transportation sector.

And in an effort to create a larger trading market for carbon, Quebec synchronized its approach with the Western Climate Initiative. Members of this group include Quebec and California, although Ontario was one of the original signatories to the initiative in July, 2008.

The Best Tools?

The design of a carbon pricing regime is critical and affects its overall impact. Key design elements include which sources and sectors will be affected, and how strong the price signal will be.

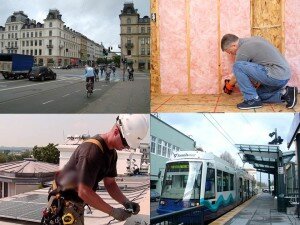

We’ve given some consideration to what tools will have the greatest ability to reduce urban GHG emissions and help Toronto achieve its carbon reductions targets. For example, a carbon tax approach would apply to 80-90 percent of urban GHG sources including emissions associated with transportation, space heating of buildings, and electricity use, not just those that come from large emitters.

On the other hand, a conventional cap & trade system for large-emitters would cover less than 10% of urban emissions; for example, in Toronto, there are only nine facilities which emit more than 25 thousand tonnes annually – the threshold cited by a previous provincial discussion paper.

As with any policy lever, the devil is in the details.

Designed with care and squarely focused on objectives, any carbon pricing tool can be highly effective. A cap & trade approach can also cover 80-90% of urban emissions if, like in Quebec, it is applied not only to large emitters but also to distributors of fossil fuels, including transportation fuels and natural gas.

A Hybrid Approach

A hybrid approach is also possible: a cap & trade system surgically-focused on large emitters complemented by other targeted pricing tools, for example an increased gas tax, increased rate-based funding for natural gas conservation and/or shadow carbon pricing in utility planning.

Selecting the right flavour of carbon pricing for Ontario is a challenge, but one thing is clear: Ontario needs to ensure that its carbon pricing approach enables its cities to accelerate reduction of urban emissions sources. Without giving cities the tools to enable urban reductions, Ontario will not reach its overall carbon reduction targets, and that will leave a bad taste in our mouths.